Background

Refugees are forced to flee from their country of residence because of conflicts and persecution according to the reasons of race, nationality, religion, political opinion or membership in a particular social group. They are persons whose citizenship from their country of origin has been ripped away, and who cannot access citizenship in their country of asylum [1]. In this sense, they cannot reach full protection and rights in the nation-state system where human rights and citizenship are binding. Thailand has hosted refugees [2] who are ethnic minorities from Myanmar for more than 30 years. Since Thailand is not a signatory to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, international law cannot apply to refugees in Thailand. Instead, Thailand has applied encampment policy under a security-led approach to confine those people in nine refugee camps along the border. In this context, refugees are illegal immigrants who have been allowed by the Thai state to live temporarily waiting for repatriation after the situation in Myanmar improves. As of December 2018, there are 97,577 refugees from Myanmar residing in refugee camps [3]. Of this number, 57,527 refugees have resided across three camps in Tak province, including Mae La, Umpiem Mai and Nu Po [4]. They can access basic needs, including food, shelter, health service and basic education provided by humanitarian agencies. Their lives are constrained and passively dependent on humanitarian aid. Those have the limitation of freedom of movement, no right to work, restricted right to higher education and the right to citizenship.

Mae Sot City

Mae Sot is a district of Tak province situated as a western border town between Thailand and Myanmar. The city is distant from Bangkok, the capital city, 492 kilometres and four kilometres from the Thailand-Myanmar Friendship Bridge which is situated as the official border check point for people crossing the border (see border town of Myanmar. The long and narrow river makes the border at this side porous. Officially, there are 12 border checkpoints [5] while it is estimated that there are about 30 unofficial channels for people to cross the border [6]. People can easily cross the river by various ways, the most popular being he crossing by boat, costing 40 baht (1.08 euro) for a round trip. According to Thai immigration data, 224,315 people from Myanmar crossed back and forth between Thailand and Myanmar at border areas in Mae Sot in November 2018 [7].

In term of governance, Mae Sot is overseen by the central government through the district administration while the city is locally administrated by the municipality. In Mae Sot, many state agencies, such as the police, immigration police, border patrol police, and military, etc., exercise their power to monitor the migration flow between Myanmar and Thailand. Identification documents such as passport, ID card and border pass play an important tool in determining who and what should enter and be expelled. Moreover, disciplinary practices at the border, such as checkpoint, checking of documents, patrolling, policing, arrest and deporting can be seen as the power of the state in this area.

In the economic aspect, the number of cross-border trading between Thailand and Myanmar at Mae Sot and Myawaddy border reached over approximately 79 billion baht (approximately 21 million euro) in the fiscal year 2018 [8] which was counted as the largest volume of the overall border trade. Moreover, numerous businesses in Mae Sot such as textile and garment factories, agriculture, restaurant, tourism, domestic work, construction, etc. require cheap labours to fulfil a shortage of Thai labours in low-skill and 3Ds (Dirty, Dangerous and Demeaning) jobs. In 2013, the Tak Provincial Office of Business Development listed 359 factories, mostly in agricultural and garment sectors, located in Mae Sot. These can be seen as a pull factor for people from Myanmar seeking economic opportunities in the city [9]. As of June 2017, Mae Sot accommodated 30,584 registered migrant workers [10] and approximately 70,000 undocumented migrant workers [11] from Myanmar. In 2010, it was estimated that migrant workers contributed approximately 4.3% to 6.6% of Thailand’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) [12]. Since 2014, the military government of Thailand has started establishing Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in Mae Sot aiming to attract foreign investors in order to boost Thailand’s economic growth because it is located on the East-West Corridor (EWC) linking to India and Southern China [13] which will attract more migrant workers from Myanmar to serve in industrial factories.

Mae Sot as a Border Regime

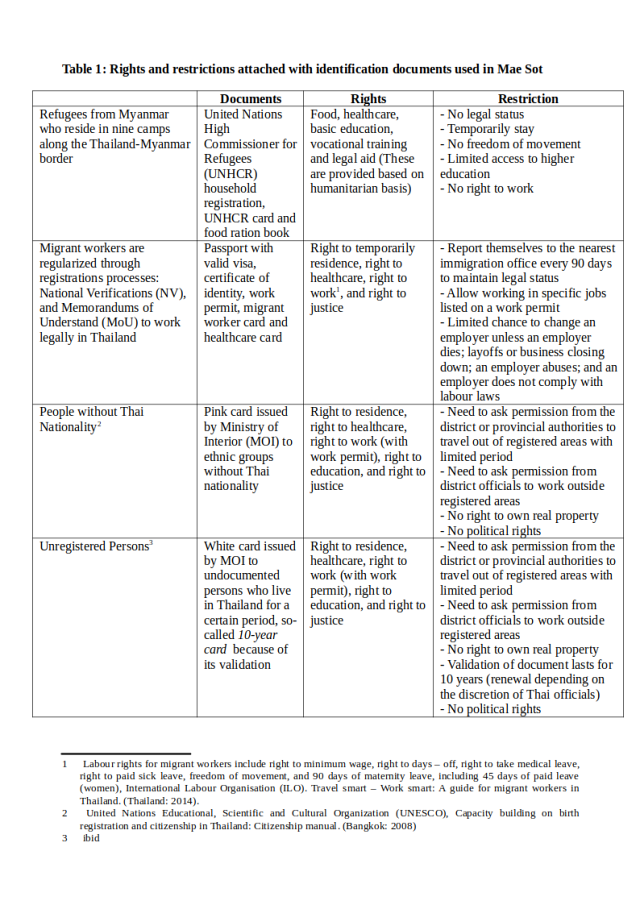

In order to simultaneously maintain national security and economic prosperity at the border, the Thai state has established a border regime including practices of identification by which people need to be identified and labelled by documents. This measure is to ensure that the Thai state can regulate the flow of people from neighbouring countries for its national security and exploit those people to boost its border economy. Thai state, therefore, includes people from Myanmar as a quasi-membership of the nation-state by bestowing partial rights on them through identification documents. In Mae Sot, identification documents such as passports, border pass, work permit, migrant worker card, ID card for people without Thai nationality, and ID card for unregistered persons are used by the Thai state to control and manipulate non-citizen population, particularly migrant workers and refugees.

In this context, document holders can access certain rights, welfares and protection; however, some restrictions attached to each document (see table 1 for rights and restrictions attached with identification documents used in Mae Sot). Without official documents, one must be deported to their country of origin according to the Thailand Immigration Act. As reported by the Embassy of Myanmar in Thailand, 34,926 Myanmar migrants without legal documents were deported by Thai authorities at the borders during July to September 2018 because of a crackdown on illegal residing and working in Thailand [14].

Mae Sot City as a Space of Negotiation

Due to the exceptional circumstance in Mae Sot, other agencies such as humanitarian agencies, transnational organizations, and cross-border businesses have functioned and exercised their power in the city to provide rights, to some degree, in the form of patron – client relationship to refugees negotiating the dominant state power. Those agencies are institutions such as civil society organisations (CSOs), medical centres, schools, and humanitarian organizations where refugees can actively engage to fulfil their needs. These agencies also issue identification documents such as organisation card, student card and medical centre card to refugees. Despite the unofficiality of these documents, they give refugees the right to mobility in Mae Sot because they are recognisable by local Thai authorities who may not arrest, according to their discretion, document holders.

As energetic agents, refugees from Myanmar have learned the exceptional characteristics of Mae Sot and employ identification documents provided by Thai state and non-state agencies to stretch their rights. I thus argue that refugees reverse identification documents by converting them from a tool of control to a tool of negotiation for rights. Following, I examine how refugees use identification documents to access the right to citizenship, the right to work, and the right to education in Mae Sot which they could not reach in the camps.

Negotiating Right to Citizenship

In the context of Thailand, refugees can integrate into Thai society through official documents issued by the Thai government. However, obtaining the documents for non-citizens is not easy because of the red tape and inefficacy of bureaucratic system in Thailand : it takes over a year to get them [15]. Apart from the national ID card for Thai citizens, ID card for people without Thai Nationality and ID card for Unregistered Persons are issued by the government to non-citizens. Refugees leverage kinship and ethnicity to get such documents and realise how they benefit from the documents. Even though the documents do not provide a full entitlement as citizenship, refugees can integrate into Thai society with partial citizenship status. A refugee told his story:

“No one recognises you if you do not have a citizenship…even the document I have is not a national identification card, the card shows that I belong to the country.” (Saw Jah (alias), interview, July 5, 2014)”

In this case, identification documents affirm local integration for refugees in a country of asylum, as one of the durable solutions. Thai government automatically permits refugees to stay in the country legally in accordance with the national law. The process of local integration can also be seen as a form of negotiation by refugees in order to access citizenship, rights, welfare, and resources [16]. However, they must compile to certain restrictions, in particular, the requirement to stay in their registered area and no proprietary rights. A refugee told a story:

“Though the 10-year card (ID card for Unregistered Persons) I have is not the Thai ID card, having something is better than nothing...It is a partial but legal status from which I can get some civil rights and freedom… I feel safe when I have the document... I can be employed and earn my living.” (Tha Dar (alias), interview, June 24, 2014).

This case study illustrate how refugees, whose citizenship they were deprived of due to conflicts in Myanmar, realise how identification documents can help them live beyond the confinement in refugee camps. With the 10-year card, Tha Dah and Saw Jah can stay legally in Thai territory. Both of them can access certain rights such as healthcare, education, employment, etc. In this sense, such identification document upgrades them from non-status, as a refugee, to partial status in Thailand even though there is a long way yet for them to go before they can access full citizenship.

Negotiating Right to Work

Due to the restriction of employment in refugee camps, refugees thus seek employment opportunities outside for their subsistence. They all understand documents such as passports, work permits and migrant worker card are important to find a job in Mae Sot and protect them from arrest and deportation by the Thai authorities. However, they realized that getting the documents was not easy because the processes take time, and money is involved. In this case, refugees have leveraged their social networks to get documents for legally working in Thailand. A refugee told his story:

“If I had stayed in a refugee camp, I would have had no future. I decided to give up my refugee status, and seek a job outside...When I tried to get money, all went to the police… It is tough if we do not have any document here...Then I asked my employer to help me get a passport and a work permit to working legally in Mae Sot… I do not need to hide and feel illegal anymore.” (Saw Tae (alias), interview, July 10, 2014)

Refugees also use unofficial documents issued by ethnic organisations to extend their right to work in Mae Sot. They have leveraged their ethnicity in networking to get a job with CSOs migrant schools and health centres in the city. These organisations issue organisational cards to refugee staffs that give them the right to travel within the city and the right to work. As a refugee working at a health centre serving refugees and migrants from Myanmar told her story:

“I know that my (medical centre) card is not official in Thailand but I use it when I need to travel from a camp to my workplace… It is acceptable by the local police… The card does not only allow me to work for my people who originated from Myanmar, but it also ensures my safety.” (Naw Ae (alias), interview, August 11, 2014)

Negotiating Right to Education

Refugees in camps have seen education as a tool to climb up social status and they accomplished this through migrant schools. The degree they received by schools in refugee camps is not accredited. Moreover, it is difficult for refugees, as non-citizens, to continue tertiary education or university level because universities and colleges in Thailand require legal documents such as passport with a student visa. With both conditions, refugees try to get recognised accreditation and citizenship. This is confirmed by Way Hay’s story of:

“I want to be a nurse in Myanmar…I want to work for my people, but my education certificates from the camp are not recognized in Thailand or Myanmar…I couldn‘t continue my education at a university with this document…as a refugee, I don‘t have a citizenship document…I also couldn‘t apply for a university without citizenship…I need to find an acceptable degree and citizenship...I really appreciate the help of a migrant school where I gain more knowledge and get an official degree to apply for university.” (Way Hay (alias), interview, July 3, 2014).

In Mae Sot, migrant schools play an important role for refugees to get an acceptable, accredited degree and use it for university application. They benefit from “Education for All Policy” by the Thai government which encourages all children, regardless of their status, to access basic education. Thai government acknowledges those migrant schools as migrant learning centres (MLCs) overseen by the Migrant Education Coordination Committee (MECC) under the Ministry of Education (MoE). As of August 2016, there are 64 MLCs accommodating over 14,000 refugees and migrants in Mae Sot [17]. Those schools recruit a few refugees in camps annually through examinations and interview. All courses, including writing, reading, mathematics, science and social studies, are taught in English in order to prepare students to get General Educational Development (GED) diploma. With GED degree, refugee students have recognized accreditation to apply for higher education at the university level where a few scholarships are available for them.

In addition to the accreditation, refugees return to Myanmar, their country of origin, in order to obtain Myanmar national ID and passport to prove their citizenship so as to apply for a university in Thailand. Migrant schools in Mae Sot can be seen as places where refugees can shift their identity through recognized educational degree and citizenship. A refugee told her story:

“(Myanmar) ID card is a shifting process for me to get more education…If I do not have the ID card and passport, I do not have any ideas how I could get a scholarship because it is available only for Myanmar citizens…such documents are important for me to move on.” (Ku Ku (alias), interview, July 18, 2014).

Conclusion

This article examines how refugees living in Mae Sot use identification documents in negotiating with a border regime. At a border, identification documents play an important role for the government to control people. Simultaneously, the documents allow holders to accesscertain rights in accordance with the law. The case study illustrates that refugees are strategic agents who learn the exceptional characteristics of Mae Sot where they use their social networks to obtain documents suitable to their needs. It is arguable that refugees have converted identification documents from a tool of control by the Thai government to a tool of negotiation for the right to citizenship, the right to work and the right to education.

Bibliographies

Agier, M. Managing the Undesirables: Refugee Camps and Humanitarian Government, trans. David Fernbach. (Malden, MA: Polity, 2011).

International Labour Organisation (ILO). Travel smart – Work smart: A guide for migrant workers in Thailand. (Thailand: 2014).

Pobsuk, Supatsak. “Negotiating the Regime of Identification: A Case Study on Displaced Persons in Mae La Refugee Camp and Mae Sot Township.” Master’s Thesis, Chulalongkorn University, 2014.

Polzer, T, “Negotiating Rights: The Politics of Local Integration. Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees 26, no. 2 (2009): 92 – 106.

UNESCO. Capacity building on birth registration and citizenship in Thailand: Citizenship manual. (Bangkok: 2008).