The main idea behind self-defence – whether it be digital, legal, intellectual or physical – is that those being “attacked” understand what is happening to them and do whatever is necessary to protect and defend themselves. This applies to many different contexts – whether it be dealing with an abusive relationship or with being arrested at a protest. The main goal is to strengthen political strategies that aim to improve society so that we may evolve towards fairer, more egalitarian societies and move away from oppression and violence. Yet certain obstacles stand in the way of these political goals: the repressive measures of the state and the police are what come to mind, as well as legislation that aims to crush dissent. Corporations, however, are also complicit: certain big “businesses” specialised in surveillance also play a part. Sometimes it’s even an odd combination, such as the case of a former secret service agent spying on a journalist for LVMH! [1] The dominant classes and the authorities use surveillance, control and repression as a way to maintain inegalitarian relations, and right now, it feels like a slippery slope down the track of authoritarianism. The question underpinning all this is, how can we keep surveillance and repressive structures in check so that we can continue to work towards building a better and fairer world.

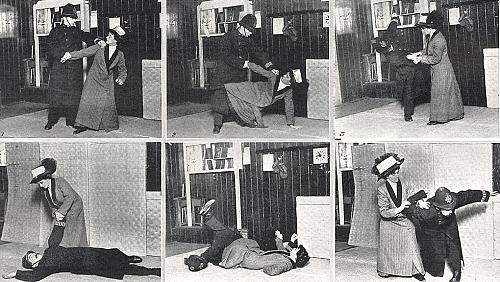

We all know what physical self-defence is: if someone attacks us, we try to protect ourselves as best we can and come out as unscathed as possible. Intellectual self-defence is also a fairly well-understood concept and requires understanding one’s opponent’s tactics, and the spin and jargon that twist how we think, thus enabling us to understand what is happening and react accordingly. Digital and legal self-defence is similar in that it’s about having a comprehensive understanding of the forces at work, so that we are able to take a step back and adjust our strategies according to the situation we are confronted with. We often see situations where people have suffered unnecessarily or been given punishments that could have been avoided with a better understanding of the practices involved. For instance, there have been cases where protestors were given a prison sentence because other people innocently took photos (without any malicious intent) at a protest and then posted the photos online, which served as evidence in court. Similarly, information circulating about asylum-seekers can be used as grounds to refuse asylum or complicate the age assessment process. The consequences of actions that haven’t been thought through and which quickly slip out of one’s control can be very serious, especially for the main targets of repressive measures (due to a country’s policies and politics). The main job of self-defence activists, then, is to inform as many people as possible of the relevant issues, enabling them to assess the risks at hand – and avoid walking blindly into traps that put power into the hands of the police and other repressive forces, as well as avoiding any unnecessary danger.

Keeping people informed and aware is an important part of this and should be tied into the idea of popular education: believing that everyone has the ability to grasp the issues at stake and is able to use and share this knowledge – even if it’s just a piece of the puzzle. You don’t have to be a legal expert or an IT whizz to understand how surveillance and repression systems work and the risks involved. But all within reason – even if you are motivated, it can be difficult to navigate a complex system such as the legal/penal system or the tech world (computing) when you don’t have the necessary training. It’s important to be able to consult specialists who are able to explain how these systems work in plain terms. Before any kind of direct action (sit-ins, blockades, etc.), there is often a “legal team” who can give advice (and potentially liaise with lawyers) on how to manage potential repression, and support activists before, during and after the event. The aim is that activists become able to gage and understand the context on their own. They should also be able to have an understanding of the players involved, the relations between these players and the actions that might ensue: a mayor is quite different from a prefect or the anti-crime squad police, which is again quite different from a judicial police officer. Understanding the context one is navigating allows one to assess the risks and know what to do if anything goes wrong. It’s important to familiarise oneself with the traps out there – such as intimidation tactics, which are used when people are held in custody and are a way to get people to confess, or trick them into giving responses that may then be used to frame them as liars or similar. Holding people in custody is a way to incriminate people who may have done nothing wrong or done nothing that would justify a prison sentence: knowing your rights and withholding information that may be used against you is an effective weapon when dealing with pressure tactics. Lastly, legal self-defence can also be about uniting around an incriminated person, supporting them and providing a solid defence case in court for them and for the collective.

Similarly, when it comes to digital technology, it’s critical that we understand the ways in which devices and tools can be used against us. The digital world and globalised social networks work both for and against us. Many of our actions and thoughts now take place on online platforms. This has enabled us to take action on an unprecedented scale. When you see protests happening in multiple cities around France at the same time and the extent to which they have gained traction, digital activism seems to be a force for good. But it is also a surveillance tool, where those waiting to clamp down on activists can hunt down the evidence they’re looking for. It’s a form of passive surveillance where everything that happens on the Internet leaves a footprint (and potentially a permanent one): our data is stored on spaces that we have no control over, such as Big Tech’s servers and other people’s computers and devices, which anyone can access, including those who want to silence us. This data, which may be harmless or of potential significance, is gathered and may eventually be used as evidence in court. It’s important to understand that information stored about us over a long period of time can be harmless one day and incriminating the next. We are undeniably living in a context where the politics of a situation can rapidly evolve and change. We may suddenly find ourselves in a compromising position vis-a-vis the state, without altering our behaviour or changing our political stance. In recent months, we have seen a host of new regulations come into force which make it possible to store data on people’s political and religious views – this includes data on individuals, initiatives, collectives and organisations. Privacy protection rules are becoming looser and looser, and it is becoming increasingly urgent that people are alert to the changing situation and understand that surveillance and monitoring is a complex issue that is now part of our everyday reality. [2]

It’s pivotal that we share our knowledge of the digital sphere and how these networks operate, and adopt an outlook that is neither naïve (under-estimating the potential dangers out there) nor excessive or paranoid (as this only has a paralysing effect that prevents one from taking action). We need to have a grounded understanding of how the digital world works and how our digital footprint may impact us and, more importantly, how it may impact others in the future. Although the current discussions around “personal data” suggest it’s an individual issue, our actions online are fundamentally also a collective issue. Because everything we do online is potentially monitored, our actions can have repercussions on those with whom we interact. Online monitoring and surveillance systems are designed to store data which serve to create social graphs and map our interactions: in this respect, anyone can be the weak link in the chain and compromise the safety of the entire group. Data collection is inherently collective, and if ever the authorities decide they need this information, individual data gathered and stored can jeopardise others. It should also be highlighted that whether the content reflects political/activist activity or whether it’s personal and may appear innocuous is irrelevant. The sheer volume of data being collected is almost as important as the content of the data itself. Moreover, it’s not always the content that is of interest. Sometimes the metadata (or connection data) is enough. Just a phone call (connection data between two devices) provides enough data to show that two people are in contact; there’s no need to know anything about the conversation (content data). The frequency of calls gives an indication of the nature of their relationship. And the time the calls were made also gives clues as to the kind of relationship it is (during office hours, after work, or before a protest). Much can be learned about two people without knowing anything about the content of their conversations.

It is, therefore, not just about being tech savvy. Having an understanding of the different forms of surveillance enables us to take “digital distancing measures” which ensure a minimum amount of security. Everyone can play a role in keeping themselves safe if they have a good grasp of the environment. It’s clear that there is no 100% foolproof strategy: digital security always involves a trade-off – weighing up the risks involved and the effectiveness of the actions undertaken. It’s about understanding the issues, accepting the risks involved and getting effective results while at the same time limiting the potential for unnecessary or avoidable repercussions.

Many people are now forced to use digital tools whether they want to or not, but don’t always have a concrete understanding of how they work, nor of the ways in which the digital sphere articulates with other social dynamics, including legal repression. The legal system stands in the way of social change and is used by those in power to crush opposition and dissent. In addition, digital technology greatly increases the potential for surveillance, which ultimately serves to provide evidence in legal proceedings. This is why it’s so important to think of digital and legal self-defence as one – as a sort of continuum: those that seek to crack down on social movements are either one and the same, or they work hand in hand (i.e., collaboration between telecommunications companies and governments with the purpose of clamping down on social movements around the world). For example, criminal investigations almost always involve some form of cellphone tracking. It enables identifying a person’s location, which cellphone towers they were connected to, the individuals they talked to, all of which give a huge amount of control to those who have access to this information. Again, digital technology and the law can work both for and against us: we can use these to our advantage and achieve great things, but they can also be used by the enemy to thwart political and social change.

People often view digital self-defence as a complex and inaccessible issue. And it’s true that it’s often presented through a tech-centric lens that is completely removed from the concrete reality and experiences of activists. IT specialists tend to go into the technical details that are inaccessible to anyone outside the IT world. Digital self-defence is also often presented as a general surveillance-protection toolbox cut off from any context. Yet it might be better to approach digital self-defence from a different angle: identify those that stand against us, the harm they can do, the risks of the planned activities and actions, and use this information to identify the relevant tools and practices. In a way, it’s about refocusing on what we want to achieve, and letting this determine the tools we need. Moving out of a tech-centric mindset also avoids putting too much responsibility on people’s shoulders and blaming them for “bad practices”. But above all, it’s important to understand that when it comes to digital and legal self-defence strategies, there are no hard and fast rules or set-in-stone advice; it’s all about context. It has to be seen as a process, not a product. There is no “one-size-fits-all” approach. It’s important to talk with those working on repression issues, encourage people to make their own decisions, drawing on concrete knowledge of the social and political circles they move in and which are constantly evolving. The idea here is to empower people to make their own informed strategic choices, not to offer prescribed solutions that could potentially put them in compromising situations, which someone from the outside may not have been able to foresee.

Yet it’s also true that we need the support of specialists; we need all kinds of expertise. The actions of activists and organisations need to be bolstered on all sides in order to minimise risks: having a grasp of the legal aspects, managing one’s digital footprint, understanding the dangers of an identity check at protests where powerful surveillance tools are being used, understanding the risks involved when using digital devices, etc. There’s power in numbers – and we need a great many individuals and groups to improve our living conditions and our societies: the more repressive our societies become, the more people we need to provide support and ensure safety. Now, more than ever, it’s critical that we identify our allies and know and recognise one another. We need to be able to identify who is skilled in what, so that we can point those requiring help in the right direction. Networking is key. In the legal realm, for instance, the Réseau d’Autodéfense Juridique (Legal Self-Defence Network) has focussed on skills-sharing and providing support for social action and movements, with good results. Digital activists are increasingly eager to develop initiatives like this one, which encourage knowledge-sharing, education and support, while also raising people’s awareness of the digital world as a double-edged sword – one that can work towards bringing about social change but also one that can be an instrument of repression. Everywhere, there are people holding digital self-defence workshops, offering training, coming up with new tools. Tech-savvy geeks who are not especially politicised need to join forces with activists who are knowledgeable about legal repercussions but not always up to speed on digital issues. It’s important that these people support and complement each other, without wasting time trying to reinvent the wheel.

These networks providing mutual aid, solidarity and support are being built up little by little, yet always in connection to concrete actions and concrete needs out there. The growing forces of repression around the world have upped our need for a strong self-defence front. There is much that we can do to ensure we have the processes and tools to keep the fight for change alive and well.