Since the death of George Floyd on 25 May 2020 in Minneapolis, protests against police violence have reached historic proportions in the United States. They have shaken the country and reverberated around the world. In France, for example, a demonstration held on 2 June and initiated by the “Vérité pour Adama” committee [named after a young man who died in 2016 after being stopped by the police] was attended by a record number of people.

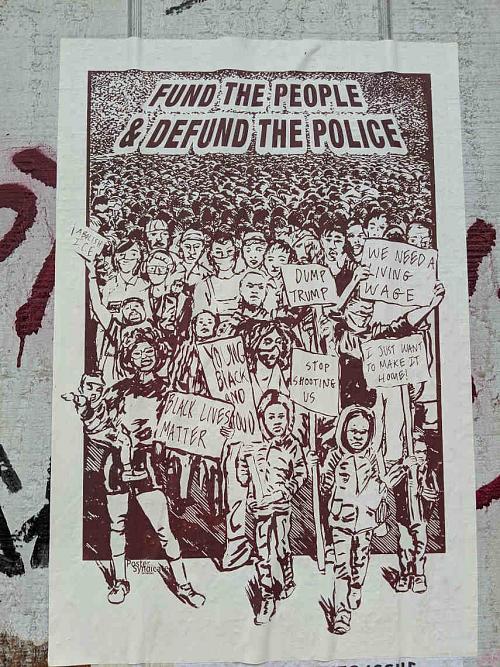

The United States protests, which initially focussed on denouncing police violence and racism, have developed into a broader movement aimed at defunding and scaling back the police.

This movement, which quickly gained traction, achieved an important victory when the members of the Minneapolis city council pledged to dismantle the city’s police department and replace it with a new community-based public safety model.

There have since been similar appeals in many other US cities, and the dismantling of the police has become a hot topic in the country, when just a few months ago it was an idea only endorsed by the radical left.

Mobilisation and significant developments in theory

The protests have led to a national campaign to abolish the police, #8toabolition. The campaign has eight core demands: defund the police; demilitarise communities; remove police from schools; free people from prisons and jails; repeal laws that criminalise survival; invest in community self-governance; provide safe housing for everyone; and invest in care, not cops.

The police institution suffered an unprecedented legitimacy crisis in the 2010s, in the wake of protests denouncing police violence against people of colour, particularly in Ferguson (2014) and Baltimore (2015), which led to the Black Lives Matter movement. Since then, several activists, researchers and groups have pushed to completely abolish the police through mobilisation and significant developments in theory.

Some abolitionist groups are active on a national scale, such as Critical Resistance, which was formed in 1998 with Angela Davis as one of its founders. Other groups are locally-based, such as the MPD150 coalition in Minneapolis. The police abolition movement has also gained momentum in Chicago where it is aligned with campaigns against prison and the penal system led by organisations such as Assata’s Daughters or Project NIA, which aim to end the incarceration of children and young adults.

It includes emblematic figures such as Mariame Kaba, whose Twitter account is followed by almost 150,000 people.

A critique of reformist approaches

The police abolition movement is critical of the reformist proposals that are usually put forward when police crimes make the headlines. These proposals include improving the training and recruitment of police officers, making body cameras (GoPro) mandatory, stricter disciplinary procedures against officers who break the rules, bans on some strangulation techniques and on shooting at moving vehicles.

Abolitionists argue that such reforms have already been introduced into the Minneapolis police department, which has often been cited as a “model” in the past.

Both abolitionist activists and academics, such as US-based abolitionist sociologist Alex Vitale, believe that liberal reforms serve to increase police resources and extend their reach, to the detriment of social care, schools, physical and mental health services. It has been noted on numerous occasions that these reforms do not actually prevent police violence. The reason for this, it has been suggested, is that police are in a position that allows them to evade the rules under which they are supposed to operate. As Mariame Kaba points out, “when police control cameras, the cameras are at the service of police violence and oppression of targeted groups within our society”.

Abolitionists believe that racist police violence is not the result of individual abuse, of misguided police recruitment or of institutional dysfunction, but stems from the police institution itself. As Fabien Jobard sums up, “In the police, you are not born a racist, but you become one.” The true role of the police institution, with its history rooted in capitalism, slavery and white supremacism, is the repression of poor and racialised populations. They believe, therefore, that any attempt at reform would be futile. [1]

“Disempower, disarm, disband”

US police abolition movements advocate a three-stage strategy: “Disempower, disarm, disband”.

Disempowering the police means reducing its budget, its personnel and its social influence. Reducing police activities involves strengthening social relations so that people can collectively manage serious situations (such as interpersonal violence) through practices such as transformative justice.

Disarming means demilitarising police forces. The police have increasingly used strategies and weapons that were previously only available to the military, a trend which has accelerated over the last twenty years. The idea is to gradually reduce the number of weapons police have access to – including so-called less-lethal weapons, such as taser guns. The final stage is the next logical step: the outright disbanding of law-enforcement agencies.

During the recent demonstrations, the slogan “Defund the police” was widely taken up and has become a rallying cry that goes beyond the abolitionist movement. The argument behind it is that budgets allocated to the police should go to other sectors and programmes that are genuinely useful to the population (health, education, transport, housing, etc.) and thus help reduce crime. Protestors are also calling attention to the need to preserve ancestral and sacred sites of Native American peoples, and to the severe pollution in many working-class neighbourhoods. They point out that the budgets allocated to deal with these issues are ridiculously low compared to the budgets given to polices forces.

Abolitionists are seeking to put an end to the expanding police and criminal punishment system, which began taking the place of social and health institutions forty years ago, and turning it into something different. According to Alex Vitale, deep racial and economic inequalities are behind the intensity of the current protests, exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, which police violence only serves to reveal.

Police abolitionism and penal abolitionism

The police abolition movement is closely aligned with the older prison abolition movement, and they are both strands of “penal abolitionism”, which aims to put an end to the penal system (police, judiciary, prison) as well as migrant detention centres and institutions for people with disabilities.

The central argument of penal abolitionism is that the penal system cannot be reformed, but is a problem in itself. This argument has been pioneered in Europe by figures such as Thomas Mathiesen, Louk Hulsman and Nils Christie. Their work reflects the development of a critical criminology which sees the criminal justice system as a set of institutions that are discriminatory, unfair and unable to respond adequately to the “difficult situations” that may occur in people’s social lives, or to address the situation, needs and wishes of victims. For these scholars, the problem is not abuse by a government, legislation or judge. The problem is the very nature of penal rationality, which is rooted in the history of the penal system. This is why it needs to be abolished, not amended. This line of argument is close to Michel Foucault’s critique of the notion of improving (or reforming) prisons and even of promoting “alternatives to incarceration”.

Abolitionists argue that penal institutions exist to reinforce and perpetuate class, racial and gender oppression. They believe that we cannot fight oppression without fighting the penal system itself.

The movement thus asks us to radically rethink social control. Instead of the criminal justice mentality that is focussed on naming and convicting a perpetrator, it seeks to establish social justice and non-punitive forms of conflict resolution based on ideals of participation, reparation and emancipation of individuals and communities. At the core of contemporary transformative justice movements is the argument that their methods can “provide people who experience violence with immediate safety and long-term healing and reparations while holding people who commit violence accountable within and by their communities”. Transformative justice organisations rely primarily on processes within communities, rather than delegating cases to experts from the criminal justice system, as a pathway to emancipation from repressive institutions. Abolitionism does not argue, as its opponents sometimes suggest, for a privatisation of justice or for the use of revenge, but for the collective management of difficult situations.

What about France?

In the United States, radical criticism of the police is rooted in the institution’s historical links with slavery, many features of which have been integrated into the current criminal justice system. In France, criticism of the police is being expressed through different narratives, reflecting the country’s own history, oppressions and struggles, i.e., the idea of a continuity between colonial power and state racism.

Penal abolitionism is not as widespread in France as it is in the United States. There are, however, campaigns against police violence which resonate strongly with what is happening in the US. The collective Désarmons-les, for example, is campaigning to completely abolish the police. In August 2020, during a meeting held on the Notre-Dame-des-Landes ZAD site, several collectives including Vies Volées, Justice et Vérité pour Babacar and Désarmons-les had a discussion about “the police, and about abolishing it and replacing it with other forms of collective management”. More broadly, families of victims of police violence in working-class neighbourhoods have been denouncing the violence and structural racism of the police and of the criminal justice system for decades. It is only recently that this cause has been taken up by other movements, such as the “Yellow Vests” movement. The media coverage of violence against the Yellow Vests contrasts sharply with what happens in working class neighbourhoods, where racialised victims of police violence are criminalised and subjected to racist attacks.

Police and protecting private property

Opponents of abolitionists often argue that the abolition of the police – and of prison – is impossible to achieve. It should be pointed out, however, that the police is a relatively recent invention in human history.

Many believe that the police serve to ensure everyone’s safety. But as studies on the history of the police and the criminal justice system demonstrate, particularly those by Michel Foucault, the police was not created as a response to crime, but to help, along with the “punishment industry”, “order” it.

As Foucault points out, the delinquent-producing criminal justice system involves, among other things, a “differentiated management of illegalisms”: designating crimes and the different punishments for each crime tends to criminalise certain categories of people more than others, and to punish them more severely. The aim of this system, according to Foucault, is not to protect us from criminals but to designate the “internal enemy”.

Across the Atlantic, a large body of research on the history of policing argues that it is closely linked to the protection of private property and white supremacism, and that it has contributed to weakening other existing forms of social control. Abolitionist theory breaks with the notion that the police is the only way to ensure the safety of citizens and argues for other forms of intervention in difficult situations.